![]()

JACK MCDONALD'S LAST FRIGHT IN A HUDSON

by Wal Bowles

| ||||||||||||||||

|

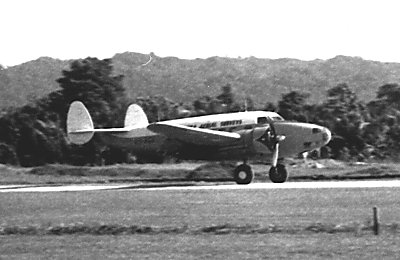

VH-AGX

landing at Madang on 27th June 1962 with the starboard engine

shut down.

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|

The

Madang fire tenders await the arrival of VH-AGX on 27th June

1962.

| ||||||||||||||||

|

INTRODUCTION

"Congratulations

on handling of Lae landing

Lou Pares

General Manager

Adastra Aerial

Surveys"

At the time

this telegram arrived in Lae, Papua New Guinea, I felt I could

have done without it, even though I appreciated the thought behind

it. Telegrams are of course confidential, but I didn't want information

to drift surreptitiously into areas of officialdom which might

prompt more paperwork. The flight from Madang to Lae and the

landing were still vivid in my mind; Jack's "fright"

was shared by all three on board, a flight which could easily

have ended in disaster.

The telegram

referred to a landing in Lockheed Hudson aircraft VH-AGX on 31

July 1962. I was the pilot-in-command, and Jack McDonald and

Brian Smith were innocent passengers. Jack was the Chief Engineer

of Adastra Aerial Surveys and Brian was the engineer assigned

to service the aircraft as part of the field crew. Lou Pares

sent the telegram a day or two after the landing, soon after Jack

returned to Adastra Head Office, Sydney. Jack never flew in a

Hudson aircraft again!

To write with

accuracy of an event which occurred some 30 years ago is a little

daunting. However the impact of the moment was so profound that

I still recall the circumstances with a mixture of feelings, not

the least being wonderment that we survived. Jack still raises

the subject occasionally in the convivial atmosphere which exists

whenever ex-Adastra crew members get together.

About ten years

ago at a civil aviation function a person who looked familiar

to me, but whose name I could not remember, introduced himself

and said: "The last time I saw you was at Lae in 1962 when

you landed a Hudson aircraft in atrocious weather conditions.

It should have been written up as an epic flight. I was an air

traffic controller in the tower at the time." It must have

made an impression on this experienced controller to remember

it as he did all those years ago; it certainly made an impression

on me!

When several

people bear witness to the same event, invariably there are discrepancies,

or at least shifts of degrees of emphasis of some aspects. Should

others who were involved read this account, their recollections

may vary somewhat from my own.

But it is not

so much the detail of the event which has remained in my memory,

even though this was a life-threatening situation with all the

attendant internal stirring of the glandular orchestra; rather

it was a sudden unexpected change in myself which is difficult

to describe - perception? consciousness? I do not know, but it

seemed to arrive of its own accord apparently from my internal

reactions.

To this day

I remain astonished by this unforgettable experience and I still

have difficulty in explaining it, even to myself.

Most pilots

experience a "close go" now and then. And "automatic

cool" is an expression sometimes used by pilots to describe

what they can hear on radio communication channels in the voices

of their fellow aviators in emergency circumstances or in circumstances

requiring a more than ordinary degree of concentration to avoid

a possible disaster. This was something different. But I have

little doubt that what I experienced is something which is common

to all people who accept a life threatening situation from which

there seems little chance of escape.

In 1962 I was

the unit manager of an aerial survey project based in Lae. I

had flown Lockheed Hudson aircraft VH-AGX from Sydney to Lae in

January of that year. The Hudson was originally a twin-engined

light bomber of a type used during World War Two. For its time,

it was an aircraft of high performance.

Our task was

the methodical photographic coverage of much of Papua New Guinea

on an opportunity basis, as often as weather conditions would

allow. Completely cloudless conditions were a requirement for

the quality of photographs demanded, but completely cloudless

conditions rarely exist in the tropics. A degree of cloud was

tolerated for survey flying in PNG, the same area sometimes being

photographed more than once with the expectation that surface

features obscured by cloud on one survey attempt might be discernible

on another.

In PNG the

warm, moist, tropical air and high, steeply rugged mountain ranges

set the stage for an interplay of factors which result in weather

conditions ranging from mist and fog in river valleys to deep,

dense cloud masses, large areas of persistent torrential rain

and violent tropical thunderstorms. Changes in weather patterns

can occur with little warning. PNG weather is subject to the

vagaries of the "inter-tropic convergence zone", the

boundary between airstreams originating in the northern and southern

hemispheres. When convergence is extreme, cumulo-nimbus cloud

can build to 40,000 feet or more. The day to day movement of

the inter-tropic zone is erratic, but it would normally be well

to the north of Papua New Guinea in July when the flight took

place.

To describe

the reason for the flight in question requires retracing the events

of the previous flight a month earlier.

THE PREVIOUS

FLIGHT - 27 JUNE 1962

The Lae crew

of VH-AGX consisted of Jack Tierney navigator, Bob Jones camera

operator and myself as pilot. (Bob Jones had been recruited in

Lae to replace Tony Burgess who, in recent weeks, had returned

to Australia to be married. Tony later became a senior airline

check captain.) Brian Smith, the maintenance engineer, completed

the field crew. Part of Brian's task was to perform a daily inspection

of the aircraft preflight, to meet the aircraft on our return,

and to attend to any unserviceabilities.

On the morning

of 27 June 1962 we took off from Lae on a survey flight over central

western New Guinea. We climbed to 25,000 feet and completed several

photographic runs. Because the weather was reasonably clear further

to the north-west, I headed for another survey area towards Wewak.

Cruising at

25,000 feet, about 30 nautical miles inland and midway between

Madang and Wewak, the starboard engine stopped suddenly. There

was no warning. The aircraft had been operating normally when

suddenly it lurched violently; I glanced towards the starboard

engine and the propeller was stopped.

This was an

unusual engine failure, unlike anything I had previously experienced.

My first impression was that the engine had seized and I was cursing

myself for having missed the drop in oil pressure. I glanced

at the oil pressure gauge and the needle was dropping rapidly

through 50 pounds per square inch (normally 75-80 psi) and I knew

then that it hadn't been an oil supply problem.

From a cruising

rpm of about 2100 the propeller stopped suddenly and completely.

Had it been a problem other than a mechanical failure the propeller

would have "windmilled". There was no windmilling;

the propeller was locked solid and the blades of the three bladed

propeller were in a normal cruising pitch.

(I learned

months later that the master connecting rod "big end', had

separated as a result of a fatigue failure of one of the connecting

rod bolts. The whole of the master and articulating rod assembly

was a mangled mass. From normal cruising rpm to stop, the engine

had rotated only 2/3 to 3/4 of a turn. With such a sudden stop

the inertia of the propeller could have torsionally failed the

propeller shaft with a complete separation of the propeller from

the aircraft. Fortunately this didn't happen. 2100 engine rpm

might seem slow in comparison to today's high performance motor

vehicle engines, but these were 9 cylinder radial engines, of

1200 horse power; slow revving but with a lot of torque.)

The violent

lurch of the aircraft at the time of the engine failure was from

a combination of a sudden absence of engine power on one side,

normal cruising power on the other, and a rolling motion from

the significant rotational inertia of the stopped propeller and

engine mass being translated into a rolling force.

It was not

a difficult situation to control. Being about midway between

Wewak and Madang I turned towards Madang and went through the

engine shut down procedure. It was unusual feathering a stopped

propeller in flight and watching the blades rotate from cruising

pitch to one of minimum drag. Once pressed, the feathering button

should have remained depressed and, by means of a limiting mechanism,

should have popped out automatically on completion of the feathering

cycle. On this occasion the feathering button remained depressed;

the cycle continued beyond the full feathered position and the

blades began to unfeather. I pulled out the feathering button

to stop the progression of the blades. Even though the blades

were then slightly out of full feather, I decided to accept this

partial drag rather than risk a further cycle with perhaps a similar,

or worse, result.

Asymmetric

flying in multi-engined aircraft requires the aircraft to be as

"clean" as possible so that aerodynamic drag is reduced

to a minimum (propeller of the failed engine feathered, landing

gear and flaps retracted and, if applicable, oil cooler flaps

and cowl gills all closed or streamlined). Adequate control of

the situation also requires full power availability on the "good"

engine, full rudder control capability, careful control of airspeed

and the more height the better. If one has to experience an engine

failure in a Lockheed Hudson, an altitude of 25,000 feet or more

is ideal!

There was ample

time to ensure the aircraft was "cleaned up" aerodynamically.

I did not attempt to maintain height because of our proximity

to Madang. The Hudson would not maintain height on one engine

above about 13,000 feet anyway. I reduced power for the descent.

Jack and Bob

at their positions in the nose of the aircraft were well aware

of the engine failure. I advised them on intercom that we would

land at Madang. The Hudson was an unpressurised aircraft, so

they needed to remain at their positions and continue using their

oxygen masks until we descended to a lower altitude.

With a gradual

descent from 25,000 feet it would not have been over-taxing the

aircraft to have landed at Lae. This would have been more convenient,

but it was inadvisable for a couple of reasons.

First, there

was a regulation stipulating that under such circumstances the

aircraft was to land at the nearest suitable aerodrome.

Secondly, the

port engine was on an "extended life" and was burning

more oil than usual for Wright Cyclones, renowned for their oil

burning characteristics at the best of times. With a normal maximum

fuel endurance of six and a half hours flight time, VH-AGX was

limited to four hours because of the oil consumption of our "good"

engine!

Better not

to push our luck, Madang was the logical choice for the landing.

I called "Madang Tower" on VHF radio. I advised them

of the engine failure, that we would land at Madang and would

arrive overhead in about 30 minutes. To the tower controller's

query "Are your operations normal?" I responded: "I

anticipate a normal asymmetric approach." The tower controller

told me later he didn't appreciate that the situation could deteriorate

rapidly until he mentioned the impending asymmetric landing to

the duty fire officer.

When he advised

the fire officer his response was: "Shit! Those bloody Hudsons

have difficulty flying on two engines let alone one, we'll have

everything standing by!" His appreciation of the flying performance

of the Hudson was in error, but I was grateful for his positive

reaction.

In 1962 the

then Australian Department of Civil Aviation (DCA) had a well

deserved reputation for professional excellence. It had the responsibility

of providing a number of services for the safety of aircraft operations.

DCA units provided services throughout PNG until after its independence.

Air Traffic Control and the Fire Service were two of these services.

I descended

with sufficient power to keep the good engine warm, applying a

higher burst of power periodically to ensure the engine was at

a safe operating temperature, important if a single engined "go-around"

became necessary. During the descent I described to Madang Tower

the type of engine failure which had occurred. This was unnecessary

and was low on my priority list. But there was ample time during

the descent and such information could be helpful for the investigation

if the landing was unsuccessful.

The equipment

referred to by the fire officer ("everything standing by")

was an antique fire tender and a converted wartime Jeep. The

fire officer was preparing for the worst happening - always a

sound aviation philosophy, and he undoubtedly had in mind two

previous Adastra accidents involving Hudson aircraft in recent

years, one at Horn Island and one at Lae. Both were making single

engined approaches and both rolled over and crashed, killing all

on board. There were different circumstances leading to each

occurrence, but history of this kind has the effect of sharpening

the concentration when making an asymmetric landing approach,

especially in a Lockheed Hudson for which the optimum approach

speed limits are narrow and critical.

Nevertheless

I enjoyed flying the Hudson. To become familiar with the handling

characteristics of any aircraft takes time and the Hudson had

a few idiosyncrasies which needed to be respected. It was an

excellent aircraft for survey work but, when most operations were

at 25,000 feet and the engines were on high power for repeated

climbs to this altitude, engine life sometimes was less than advertised.

Jack and Bob

vacated the nose of the aircraft during the descent and Jack stood

at the right hand control seat position. (For survey flying the

right hand control seat was removed to allow the navigator and

camera operator access to their operating positions in the aircraft's

nose. The Hudson was operated on survey work as a single pilot

aircraft and was flown from the left hand control seat.) It was

always supportive to have one of the other crew members up front

and Jack was particularly helpful on this occasion. We had exchanged

a few comments about the quantity of oil being burned by the port

engine on its "extended life" before Jack went back

to the cabin area to strap himself in for the landing.

I have no doubt

that Jack and Bob were thinking about the earlier Horn Island

and Lae accidents. They were well aware of the possibility that

the landing might not be normal, but both displayed a resigned

"Oh well, you can handle it" confidence which my gastric

juices at the time might well have denied. On our single engined

descent we arrived over Madang at about 3000 feet altitude and

I planned the landing approach towards the east-north-east, runway

07. The Madang runway length was 4,500 feet, adequate but not

generous for a Hudson asymmetric landing. The touchdown was smooth;

it was further into the runway than I would have liked, but far

better than undershooting and having to apply high power on the

landing approach.

The aircraft

stopped on the over-run and the fire tender, which had been positioned

adjacent to the runway, was now following closely. Fortunately

Jack was able to get out of the aircraft before the tender arrived

and he managed to stop the fire crew covering our "good"

engine with foam. The "normal" exhaust smoke trailing

from the port engine led them to believe it was on fire!

SYDNEY MORNING

HERALD 2/6/95

"PLANE

OVERSHOOTS RUNWAY

PORT MORESBY:

A plane carrying 35 passengers overshot the runway at Madang

Airport on Papua New Guinea's north coast and slid into

shallow water on the edge of the harbour on Wednesday.

None of the passengers or the four crew members was injured.

- AAP"

("The

runway was not generous" - a recent news article)

VH-AGX was

towed to the tarmac and I then needed to make arrangements for

a replacement engine. Communication with Sydney was only by cable/telegram.

Jack McDonald, in Sydney, on receipt of the telegram had difficulty

in accepting that the starboard engine had failed. He was well

aware of the high oil consumption of the port engine and he believed

that the port engine had probably seized. In any event he made

arrangements for a replacement engine to be shipped to Madang,

but it would be a month before it arrived.

After the landing

at Madang on 27 June 1962 Jack Tierney, Bob and I went back to

Lae by Mandated Airlines to await the arrival of the replacement

engine.

My wife, Margaret,

and our two children, Wendy and Robin, had been with me in Lae

since February of that year. (Cameron, our third child, was not

born until 1965.) Adastra Head Office decided to relocate VH-AGX

for another contract in Australia after the engine change, so

I made arrangements for Margaret, Wendy and Robin to return to

Sydney by the TAA DC-6 service before the replacement engine arrived.

It was a wrench to see them off at Lae Airport.

ONE MONTH

LATER

When the replacement

engine was due to arrive in Madang by ship, Jack McDonald flew

to Lae from Sydney by the scheduled TAA DC6 aircraft. On his arrival

we (Jack McDonald, Brian Smith and I) flew to Madang by Mandated

Airlines to change the engine in VH-AGX. Jack Tierney and Bob

Jones remained in Lae.

Jack McDonald

arranged to use one of the Mandated hangars on Madang aerodrome

for the engine change, which took the three of us the best part

of two days. Jack noticed a slight bend in one of the push-rod

covers of the failed engine. There was no doubt about the mechanical

nature of the engine failure from the immovable propeller, but

it was further confirmed by the bent push rod.

The engine

change proceeded without difficulty, although it needed Jack's

engineering expertise and practical flair to provide the answers

to a couple of discrepancies between the control linkages of the

old and new engine installations.

Brian Smith

was a competent young engineer, but Jack's vast experience knowledge,

ability, his understanding of DCA requirements and his determination

of what was reasonable and safe in circumstances when it was impossible

to "go by the book" on every occasion in remote locations

was masterful. As one who spent most of his time in the field

I was unaware of most of what occurred at the Sydney base. I

hope Jack's many engineering talents and his willingness were

fully appreciated by Adastra management.

On the morning

of 31 July 1962 the installation of our replacement starboard

engine was almost complete. We checked out of the hotel expecting

that we would be on our way back to Lae about mid morning. I

would air test the engine at the same time. The final split pin

and piece of locking wire secured, VH-AGX was wheeled out onto

the tarmac and the ground run of the replacement engine was satisfactory.

And this is where the story really begins.

FLIGHT PREPARATION

MADANG - 31 JULY 1962

I completed

weight and balance calculations and prepared a load sheet. Jack

decided to run the port engine while I submitted a flight plan.

It was mid-morning

when I went to Madang Tower to obtain a weather briefing and to

submit a flight plan for the flight to Lae.

On my way to

the Tower, I spoke to a Mandated Airlines DC3 crew who had landed

at Madang only about 15 minutes previously on completion of a

flight from Lae. As is usual in PNG, pilots invariably ask other

crews about weather conditions they have encountered. The Mandated

crew advised that they had flown up the Markham Valley without

any difficulty and that the weather at Lae and throughout the

flight had been fine with no problems for visual flight.

Visual Flight

Rules (VFR) applied to all Adastra flights. VH-AGX was minimally

equipped for instrument flight and was not approved for flight

under the Instrument Flight Rules (IFR). All survey flights required

clear weather for photography. When one task was completed and

the aircraft needed to be repositioned for another survey area,

if the weather was unsuitable it was more economical to wait for

a day of good weather than for the company to have the ongoing

expense of IFR equipment and its servicing as well as flight time

costs for pilot training and periodic currency checks.

The weather

forecasts en route and at Lae were consistent with the information

I learned from the DC3 crew. Madang weather was fine with normal

cumulus build up and a reasonably high base. The Markham Valley

was the shortest, most direct route and was the appropriate way

to plan. Allowing for a "dog-leg" to enter the Markham

Valley, flight time in the Hudson would be about 45 minutes.

The Finisterre Mountain Range ran along the northern coast of

PNG from a position north of Lae to a position south of Madang

and the range, up to some 13,500 feet elevation, formed the northern

boundary of the Markham Valley. From Madang aerodrome, weather

towards this range appeared reasonably clear. If flight through

the Markham became inadvisable because of cloud buildup, the alternative

was a longer route coastal via Finschhafen, almost double the

distance.

There was no

problem with fuel reserves if the longer route became necessary,

or to return to Madang via the same longer route if Lae weather

deteriorated. Based on hours flown since last refuelling and

a check of the fuel gauges, in theory there was fuel sufficient

for 4 hours - 3 hours 15 minutes flight plus 45 minutes reserve.

In fact there would have been something less than this, mainly

because of evaporation during the period the aircraft had been

standing at Madang. I considered refuelling at Madang but decided,

in view of the existing fuel state and the relatively short flight

time, to delay refuelling until after we landed at Lae.

Aircraft fuel

tanks are normally kept filled to capacity, especially in the

tropics, because of condensation. Water in fuel is to be avoided

at all costs and our fuel draining after VH-AGX had stood for

so long was thorough. With the current weather forecasts the

minimum fuel requirement would have been 90 minutes - 45 minutes

flight fuel plus 45 minutes reserve. I was satisfied we had sufficient

for Madang - Lae with a return to Madang if necessary and with

generous reserves. The port engine oil tank was topped up to

ensure we had a safe oil endurance.

I planned via

the Markham Valley with an estimated time of departure (ETD) 30

minutes from the time of lodgement of the flight plan. This would

allow a comfortable period for Jack to run the port engine and

for final loading of tools and equipment. If the aircraft did

not taxy out within 30 minutes of the ETD, the flight plan would

be invalid and submission of another flight plan would be required.

Walking back

to the tarmac area I could see that Jack was having difficulty

in starting the port engine. The engines were normally started

with the aircraft's batteries. If one engine was difficult to

start, starting the other and using generator power was the next

step. On this occasion the starboard engine was stationary and

Jack had arranged to use a battery cart. I knew there was a problem.

The port engine,

having been subjected to tropical moisture for a month without

being run, was being more than ordinarily difficult.

Ted McKenzie,

Adastra Operations Manager and Chief Pilot, had briefed me thoroughly

for the New Guinea operation and had commented on this moisture

problem. He advised that, in the event that weather was unsuitable

for survey for lengthy periods, I should fly the aircraft every

week for an hour to keep the ignition system from becoming saturated.

If the weather was unsuitable for flying, then to run the engines.

Weather was rarely suitable for survey and it was essential for

the aircraft to be in readiness for those rare occasions. I made

a practice of flying the aircraft for 30 minutes twice each week.

Ted was an

exceptional pilot and an excellent check and training captain.

When some action was needed in flight which was a little out of

the ordinary, I was quietly grateful to Ted on more than one occasion

for his sound advice and for his white knuckle, perspiration producing,

fly-to-the-limit flight checks. Ted did everything he could to

ensure that all of his pilots would be able to handle the Hudson

competently under all circumstances, and particularly after the

unfortunate accidents at Horn Island and Lae. My six monthly

flight checks often concluded with my clothing absolutely saturated

with perspiration and without a dry pocket in which to put my

flight check certificate of competency.

So, having

not been run for a month, the port engine ignition system was

breaking down with tropical moisture and was difficult to start.

How long it would take to dry the system sufficiently to get the

engine started was uncertain. (There was no WD40 in those days!)

When the port engine continued its cantankerous behaviour I cancelled

the flight Plan, explaining to the tower controller that I would

re-submit the plan after the port engine was started.

There was yet

another setback for our flight to Lae. On my return from flight

planning, the period of validity for HF radio servicing was found

to be expired and an approach to DCA by Brian for a concession

was not approved. Jack McDonald made a second approach, explaining

that radio servicing facilities were at Lae and were unavailable

at Madang. It would be expensive to fly a radio serviceman from

Lae to Madang for what would probably amount to a radio check.

DCA granted a concession for a single flight, Madang to Lae, subject

to a satisfactory preflight HF radio check.

The radio ground

check proved satisfactory, but the HF radio was to be a problem

later in the day. Communications between Air Traffic Control

units were often difficult in 1962 and en route communications

relied primarily on HF radio. VHF was far better quality in terms

of clarity, but was limited to “line of sight" (no benefit

of satellites!).

It was after

1600 hours EST (4 pm) before the port engine started, roughly

at first but it was soon firing evenly after it began to warm

up. I had almost decided to abandon the idea of flying to Lae

that afternoon, but there was still time, and after all, the weather

was fine throughout - or so I thought.

If a diversion

became necessary I would need to return to Madang. It would have

been stretching it to get to Port Moresby. This would have involved

a climb of some 15,000 feet over the Owen Stanley Ranges and in

any event there was insufficient time before last light to get

to Moresby. It is always desirable to have plan B in mind when

planning a flight, and perhaps plan C as well. For example there

is always a possibility that a runway can be closed just prior

to landing because of a preceding landing aircraft with a blown

tyre. Anticipating such events helps avoid that “thinking feeling"

if circumstances change suddenly.

As soon as

the port engine was operating satisfactorily on its ground run

I went to the tower to submit another flight plan. There was

no weather forecaster at Madang but from the tower I was able

to speak by radio directly to the forecaster at Lae. I jotted

down the forecast which hadn't altered significantly from the

morning forecast. It was satisfactory for a VFR flight with light

and variable winds throughout below 5000 feet.

I requested

an actual observation at Lae and this was also satisfactory, visibility

15 miles, main cloud base 5000 feet with 1/8 of scud at 1000.

1/8 scud at 1000? Unusual, must be the low scuddy cloud which

often formed over the Markham River, just south of Lae. I asked

the forecaster which route appeared clearer, coastal or via the

Markham Valley. He indicated that via the Markham should be the

clearer route.

Night flying

was not permitted in PNG and all flights were to be planned with

an ETA of at least 10 minutes before last light. At this stage,

last light was becoming a consideration. The end of daylight

in the tropics is significantly different from middle and high

latitudes. The end of daylight charts take into account a certain

amount of twilight after sunset, depending upon latitude. The

higher the latitude, the more twilight until, above the arctic

and antarctic circles there is "land of the midnight sun".

In the tropics there is very little twilight; soon after sunset

darkness falls like a blind.

Last light

at Lae was shown to be 0836 hours GMT (1836 EST or 6.36pm). If

I set course by 0640 GMT, (4.40 pm) and flew to Lae via the Markham.

I could still return and land at Madang about 25 minutes before

last light if Lae weather deteriorated. The requirement to plan

with an ETA at least 10 minutes before last light could be met

comfortably.

It looked good.

Why did I have this lousy feeling that I ought to wait until tomorrow?

THE FLIGHT

I walked briskly

back to the tarmac and Jack and Brian were ready to go. The battery

cart had been wheeled away. Jack was in the control seat with

both engines operating. Brian boarded the aircraft behind me

and closed the door. Jack vacated the control seat and I strapped

myself in. I wasted no time in completing a pre-taxy check, taxying

to the holding point and conducting an engine run-up. We took

off from runway 07 and I obtained approval for a right turn towards

the Markham Valley. No problems with the replacement engine;

it was performing beautifully with all temperatures and pressures

well within their normal range. Our departure time was 0640 hours

GMT.

Soon after

departure and with a better appreciation of general weather conditions

with height, it became apparent that we would be unable to enter

the Markham Valley because of cloud build up, even with a significant

diversion to the north western end of the valley. From a base

of about 3000 feet, towering cumulus cloud covered the rising

Finisterres completely, cloud tops being 20,000 feet or more.

Most IFR aircraft avoided the direct track Madang - Lae. It required

a cruising level of at least the minimum safe altitude of 16,500

feet because of the high terrain. I altered heading coastal and

calculated an ETA Lae of 0800 GMT, 36 minutes before last light.

The ETA for

Lae was closer to last light than I liked even though it was 26

minutes more than the 10 minute minimum required. Last light

graphs do not take into account factors such as the terrain surrounding

a location, a cloudy sky or visibility less than unlimited. Significant

cloud cover, poor visibility or high ground to the west can result

in the earlier onset of last light. However the Hudson cruised

at 170 knots and, with light and variable winds forecast, the

ETA was likely to be accurate. At least I could continue for

awhile and still return to Madang before last light if the weather

deteriorated.

Full reporting

procedure is required for all flights in PNG. I called Madang

Tower on VHF and advised of our change of plan, that we would

track coastal to Lae via Finschhafen. I gave my ETA Saidor (on

the coast about 50 nautical miles (nm) from Madang and 65 track

miles after taking into account our initial track towards the

Markham Valley) of 0703 and Lae of 0800 (1800 - 6.00pm). This

was acknowledged. I reported to Madang approaching Saidor and

we were still within VHF range at our cruising level of 4,000

feet. My next report would be a scheduled reporting time, approximately

midway between Madang and Lae at 0720 GMT when we would be about

100 nm from Madang with about 55 nm to run to Finschhafen.

To remain “legal”

relative to last light, we could stay airborne until 0826, 10

minutes before last light. That is, with a departure time of

0640 we could fly for 106 minutes. So our "point of no return"

based on last light considerations and light and variable wind

conditions was 0733, being 53 minutes after our departure time.

If we needed to return to Madang this would give a couple of minutes

margin because last light at Madang was a little later than at

Lae.

Why did I have

this uncomfortable feeling that I ought to be returning to Madang?

In PNG particularly,

I always liked to “look over my shoulder" with time to divert

and land at an aerodrome I had overflown or where I knew the weather

to be suitable. Runway lengths and surfaces in PNG in 1962 limited

the operation of Hudson aircraft to only five aerodromes; Port

Moresby, Lae, Madang, Wewak and Rabaul.

My practical

options were to continue to Lae or return to Madang.

I called on

HF at the scheduled reporting time of 0720 GMT and received no

reply. I called again and asked for actual weather conditions

at Lae. No response. I called on VHF but we were then too far

from Madang for VHF transmissions to be possible and we were certainly

too far from Lae, especially with the Finisterres blocking our

line of sight. Tracking along the coast we were cruising at 4000

feet below a broken cloud cover.

I called “any

aircraft" on VHF hoping for someone to relay our position

but there were apparently no other aircraft in our area or on

our frequency. I tried another HF frequency, but still no success.

The fuse for the HF equipment looked satisfactory but I changed

it anyway. Try another microphone. Another radio check, no response.

Damn! We were

half way to Lae, our groundspeed was consistent with the flight

plan and the weather ahead looked quite reasonable. Continue

to Lae or return to Madang? Radio failure requirements were to

proceed to the nearest suitable aerodrome, land, and telephone

air traffic control. The nearest suitable aerodromes were either

Lae or Madang because we were midway between the two.

Radio servicing

facilities were at Lae but not Madang. The weather en route and

at Lae was fine (so I thought), we needed the HF radio serviced

at Lae, Jack needed to return to Sydney without too much delay,

and our base accommodation was at Lae, in the DCA mess. The replacement

engine was performing well and all information available indicated

that logically we should go to Lae. Why this strong gut feeling

to go back to Madang?

I called Lae

again, advising that we were not receiving on HF and we would

continue to Lae, ETA 0800 and, “if receiving this transmission,

please advise the Lae weather conditions". No reply. I

had no way of knowing whether my HF transmitter was functioning,

but radio fail procedure requires this assumption so that air

traffic control may have some information to work on.

We were approaching

our point of no return (PNR) based on last light, 0733. I descended

to 3000 feet and the weather ahead looked good, hazy, but the

visibility was about fifteen miles. Our PNR came and went and,

with an uncomfortable feeling of resignation based on nothing

but a lousy gut feeling, I committed the flight to continue to

Lae. Soon the cloud layer, about 500 feet above us, seemed to

be lowering and I descended. The weather still looked satisfactory

ahead with no observable deterioration. I continued the descent

down to 1000 feet and, looking down at the kunai grass it was

bent over at right angles towards us. Obviously a strong headwind

at the surface and certainly not the light and variable winds

forecast, at least not in this area. We could be a minute or

two later at Lae because of this and our last light margin would

be reduced. My gastric juices acknowledged.

Soon after

passing our PNR, a general weather deterioration was apparent

in the distance with widespread areas of rain. At that stage

I could almost see Finschhafen near Cape Cretin, the most prominent

northern "bump" of PNG, but Finschhafen appeared to

be almost obscured by rain. It was too late to return and land

at Madang before last light. Lae it had to be.

What about

a landing at Finschhafen? A natural surface grass strip, probably

saturated with water and unsuitable for Hudson operations even

in dry conditions. Finschhafen was not on the list of approved

aerodromes. I would have considered a precautionary landing there,

but getting closer to Finschhafen and flying now well below 500

feet to remain in visual contact with the ground, rain squalls

obscured Finschhafen airstrip.

Blast. We

were about three minutes behind our ETA Finschhafen of 0741.

I flew slightly inland, across the corner of Cape Cretin, abeam

Finschhafen. There was low lying land for a few miles inland

at this point and I flew towards the Huon Gulf coastline which

I could see, with Finschhafen, or where I assessed Finschhafen

to be, about three or four miles to our left. This "short

cut" would reduce our flight time by a minute or two and

would help make good our ETA at Lae.

The foothills

of the Finisterre Ranges to our right were totally obscured by

cloud and it was black ahead. On a previous flight from Rabaul

to Lae there were large areas of localised deteriorated weather

off the coast from Finschhafen and I was hoping the Lae aerodrome

forecast of clear weather was accurate.

Perhaps the

weather would open up after I reached the coast and got closer

to Lae; after all, the Lae actual weather just before we departed

from Madang was good. But all I could see ahead were worsening

conditions. My decision to continue the flight beyond our PNR

was not made lightly but overflying Cape Cretin I thought "cretin"

was an accurate description of my self image at that time.

I needed to

descend well below 500 feet to maintain forward visibility. We

were running into dense rain squalls. The cloud was dark grey

with an indistinct base, not far above us. As well, daylight

was fading; the cloud mass over the ranges to the west of the

Huon Gulf must have been very dense and deep. The sun would have

been low on the western horizon somewhere above this cloud mass,

and it would have been also behind the ranges to the west, contributing

to the earlier onset of last light.

Apart from

being illegal, climbing into cloud could have been disastrous.

The lowest safe altitude for an IFR flight approaching Lae from

the Huon Gulf was 3400 feet. If I climbed into cloud, a descent

in clear weather to seawards off Lae looked extremely unlikely.

If there was little clearance between the cloud base and water

surface, a descent in darkening conditions could result in the

aircraft crashing into the water before the water surface became

discernible. It was imperative to maintain visual contact with

the ground or water.

VH-AGX was

equipped with basic attitude instruments and a single ADF, an

instrument which, when tuned to a ground station (NDB), would

indicate the direction of the station from the aircraft. It was

a useful navigation instrument, but it had its limitations and

was known to point to thunderstorms at times instead of to the

station to which it was tuned. (When flying in the RAAF I had

experienced this.)

I tuned to

Lae NDB and received a positive needle indication. We were too

far from Lae to identify its transmitted signal but its steady

indication was supporting.

I needed to

stay below the amorphous cloud base to maintain forward visibility.

But forward vision was difficult in the Hudson with its flat,

sloping windscreen panels. Rain would strike and spread on these

flat surfaces, virtually obliterating forward vision. (Curved

windscreens on modern light aircraft help overcome this problem.)

There were

no windscreen wipers. I opened the port sliding cockpit window

for better external vision.

At this stage,

flying very low across swampy mangroves and with no indication

of improvement in any direction, I fleetingly considered the possibility

of putting the aircraft down on any reasonably flat area. No,

it would be better to go back and try Finschhafen if I could find

it, or put the aircraft down on an area of kunai grass - a bit

better than swamp crocodiles; but what if we were to overturn

on touchdown? The whole area was pockmarked with craters from

the World War Two bombardment, too lumpy for a safe precautionary

landing.

Climb through

the murk and go to Moresby? Moresby would have runway lighting,

and I had by then put behind me the niceties of trying to stay

“legal". That is, the aircraft's instrumentation was not

approved for instrument flight and I had not held an instrument

rating since leaving the RAAF some 3 years previously. But this

was a question of survival; we were far from legal as it was regarding

specified visibility and distance from cloud and ground for a

VFR flight but there was little option. And if there was a softer

option than rock-filled cloud I would take it, so stuff the regulations.

But Moresby

was too far; we would arrive there at least an hour after last

light. And, assuming our radio problem was not common to both

VHF and HF and our VHF was serviceable, the air traffic controllers

would all be at their favourite watering holes long before we

had even cleared the Owen Stanleys and were within VHF range.

As well, the fuel quantity remaining was doubtful for the distance,

and I didn't want to check the serviceability of the aircraft's

internal lighting which probably hadn't been used for years.

If it worked it would wreck my external vision. It had to be

Lae.

Fleeting thoughts,

pelting rain, obscured windscreen, about 50 nm to run to Lae,

flying about 100 feet above the ground, getting darker, bloody

hell Bowlesie, you've stuffed up this time, looks like you've

written yourself off with Jack and Brian and written off the aircraft

as well. I felt a twinge for AGX, the fastest aircraft of the

fleet. I accepted that we had next to no chance of recovering

the situation I had placed us in. I believed our chances of flying

into the real estate were very high indeed. I accepted death.

And then IT

happened.

My impression

at the time was that something, something intangible outside myself

enveloped me and permeated my entire being. It was instantaneous;

the moment I accepted death as virtually inevitable there was

this all pervasive feeling of unimaginable calmness. And a second

or two later: "But we are not dead yet - perhaps we have

a 1% chance of getting away with this. Let's see what I can do

with this 1%.

I felt like

someone with his back to the wall, intense concentration, calculated

efficient actions, yet all the time this unusual, unbelievable,

peaceful serenity without a word from my gastric juices. Perhaps

they had all been used up.

I reached the

coastline and paralleled the coast towards Lae, about 50 nautical

miles ahead. At this stage we were flying below 100 feet and

probably below 30 feet for much of the time. Wind squalls were

visible on the sea surface which was flattened by heavy rain.

The dark grey metallic colour of the sea merged with the low,

indeterminate cloud base. In the fading light the torrent on

the windscreen totally obscured forward visibility. We were about

half a mile to seaward.

At about this

time Jack and Brian came up front, viewing the weather with some

concern. I asked Jack to open the starboard side window. By

now the open side windows were our only means of visual reference.

To our right, through the restricted opening of the starboard

window, the dark grey of the water merged with the darkness of

the vegetation along the coast. I concentrated on staying out

of the water and getting some idea of attitude from an occasional

glance at the artificial horizon, but mainly from the appearance

of the terrain on our right. From my position in the left hand

control seat the starboard wing obscured my view of the coastline

for much of the time. By banking the aircraft occasionally I

tried to identify a coastal feature, but I found this impossible.

The colour

of the dark coastal vegetation on rising hills mingled with the

indistinct cloud base, which seemed less than 100 feet above the

water with heavy rain and scud beneath.

There was no

possibility of obtaining a visual fix; to look from the ground

to the map was risking inadvertent water contact. It required

all my concentration to stay clear of the water and clear of the

ground when we passed over a small headland. Yet all the time

there was this incredible feeling of peacefulness, totally inconsistent

with the situation.

I continued

to call Lae Tower on HF and VHF and finally, about 30 miles from

Lae by estimation, there was a welcoming response: "Alpha

Golf Xray, Lae Tower, we've been calling you for some time, go

ahead."

I recognised

the tower controller's voice, a somewhat dour ex-RAAF Wing Commander,

Phil Graham. I replied: "Alpha Golf Xray now approximately

three zero miles from Lae, coastal, estimate Lae at zero three,

what are your weather conditions?" There was concern in Phil’s

usual monotone when he replied simply: "The weather is poor."

This was a

particularly unusual Air Traffic Control transmission. Inbound

aircraft at 30 miles usually receive landing instructions such

as: "AGX runway --, the wind --, QNH ---, report one zero

miles." "The weather is poor" meant the weather

was bloody awful. I asked Phil: "What’s the visibility?"

He replied: "About a mile". If my heart hadn't dropped

to my boots about 20 minutes previously it would have sank; yet

there was still this extraordinary, almost detached feeling of

tranquillity. There was obviously no improvement in the weather

at Lae; perhaps it was even worse than that which we'd been experiencing

since before passing abeam Finschhafen.

“Lae Tower

this as Alpha Golf Xray. What is the landing direction?"

Phil was remarkably quiet. "The wind currently favours 32,

and the QNH 1008”. I learned later that Phil had telephoned Jack

Tierney and invited him to the tower "to see these galahs

prang. There’s no way they are going to be able to land in this."

So Phil didn't

waste words. If the Hudson was going to prang, why waste breath

on landing instructions? But the weather would have closed the

aerodrome and Phil couldn't legally issue landing instructions.

However there is no way he would have denied assistance to an

aircraft in our circumstances.

Soon after

this communication about 30 miles from Lae (I had no idea of precisely

where we were) I selected the landing gear down. Gear down lowers

the nose position slightly for level flight and is supposed to

give a slightly better forward visibility. Handy if we happened

to encounter a break in the rain to give us some forward visibility!

Because of what happened a little later I was pleased I took this

action.

I obtained

an identifiable signal from Lae NDB and the ADF needle was pointing

ahead steadily. Was it pointing to Lae or towards a thunderstorm

cell?

At least there

was no visible lightning to suggest thunderstorm activity; it

was more than enough to cope with the torrential rain and dense

nimbo-stratus cloud almost to the ground and water surface without

further complications.

I figured our

ETA Lae would be a little later than planned because of the headwinds

at low level along the north coast, shown by our loss of a few

minutes abeam Finschhafen. However our heading change from south

easterly to westerly after Finschhafen could have resulted in

a tailwind component which would make up some of our loss. Again,

the reduction in speed for gear down would make us a little later,

but not more than a few minutes. Impossible to identify any landmarks

in this torrential downpour, let alone calculate a revised ETA.

Jack remained

at the starboard window. He had a slightly better view of the

terrain than I and, even though nothing was said, I knew that

he was looking out for possible obstructions. Saying anything

was pointless anyway - nothing could be heard above the noise

of the engines with the side windows open. I was grateful for

Jack's presence. From my familiarity with the general area I

knew there were no obstructions as long as we hugged the coast.

If we missed seeing Lae and overflew the Markham River, we would

be faced with the spine of the Owen Stanleys rising to over 9000

feet just beyond the Markham. We would use up our final 1% if

I missed Lae. I needed to keep the aircraft low to get what visibility

I could from the side windows. But even at a reduced cruising

speed, necessary with the landing gear down, there would be insufficient

manoeuvring distance to avoid rising terrain if it loomed out

of the murk ahead. Slowing the aircraft further could help a

little, but with darkness fast approaching I was reluctant to

reduce speed, so while I could see the coastline and remain just

to seaward of it I would be making the most of our 1%.

Brian went

back to the cabin, put on a pair of headphones and listened to

the radio transmissions.

As a minimum

runway length, 4000 feet was required for the Hudson. This requirement

could vary depending on surface wind, temperature and other atmospheric

conditions. The landing charts were based on normal flapped approaches

and the 4000 feet minimum length was accepted as a safe landing

distance for Hudson operations. Lae runway, aligned 320/140 degrees

was 4000 feet in length with jungle at the western end and a drop

of about ten feet to the sea at the eastern end. The Lae landing

chart showed the aerodrome elevation as eleven feet above mean

sea level.

The "Tenyo

Maru” was a Japanese vessel which sank in the Huon Gulf during

World War Two. It was run aground on the edge of a steeply sloping

reef or shelf just a few hundred metres off the eastern end of

the Lae runway. Its bow, angled up steeply, was perhaps 30 feet

above the water. It was an excellent point of reference when

approaching Lae, especially in conditions of haze or reduced visibility.

On final approach to Lae runway from the sea the Tenyo Maru was

about 100 feet to the left of the approach path.

But where was

Lae? The ETA of 1803 I had passed to Lae Tower was to accommodate

the time loss observed near Finschhafen, even though I felt we

may have picked up a little, both from "cutting the corner"

and from a possible tailwind component after the heading change

near Finschhafen. I needed to reduce the indicated airspeed to

125 knots to select the gear down, which I had done at an estimated

30 miles from Lae, and this speed reduction over that distance

would account for a loss of a few minutes.

My expectation

was that we would reach Lae no later than about 1802. It was

now 1802 and no sign of Lae. In this miserable weather and fading

light I was feeling a little doubtful whether we would be able

to see Lae, even from 100 feet. Let's hope we might see a few

lights in some of the homes and buildings on the higher ground

which I knew to be to the north of Lae aerodrome. No doubt the

Mandated Airlines Club on the hill above the aerodrome would have

its normal patronage and its lights might be visible, providing

it wasn't enshrouded in low cloud.

1803, nothing.

And now 1804. Where the hell was Lae? Nothing except continuous

torrential rain, an obliterated windscreen, low cloud and scud,

an indistinct landscape to the west and darkening conditions.

Jack and I were oblivious to the rain through the open windows;

not all of it was whipped away by the slipstream. At least the

deafening roar of the engines was comforting. By this time I

began to wonder whether we had passed Lae and were heading for

the ranges across the Markham. No, not yet anyway because we

were still following the coastline and heading generally west.

The Huon Gulf coastline swung to the south and then south-east

just beyond Lae. My mental alertness was acute. We didn't need

the 9000 feet ranges across the Markham to suddenly terminate

the flight, tracking over coastal projections, a tall tree might

achieve a similar result.

I began to

alter my concentration from the starboard window and to scan the

water to the left. Perhaps I would spot the Tenyo Maru, or less

palatable, terrain too close to avoid. But the ADF needle maintained

its steady indication ahead. The ADF in VH-AGX had always been

reliable and Lae NDB was transmitting a strong signal so, believe

it, Bowlesie! I mentally put on "hold" the possibility

that the ADF needle may be pointing to a thunderstorm cell.

ETA updates

are required if the calculated ETA varies by more than two minutes.

We were a minute over our revised ETA of 1803, so I called the

Tower again and gave another revision to 1806, purely by guesstimation.

We were still hugging the coastline but precisely where was anyone's

guess.

1806 and still

no sign of Lae. This was crazy, as crazy as this feeling of incredible

calmness in this situation. At the speed of the Hudson, wind

conditions need to be significantly different from forecast to

alter the ETA to any extent. On one occasion I flew for about

5 hours from Mackay in Queensland to Sydney and arrived within

a minute of the original ETA calculated on departure. A six minute

variation over the relatively short flight from Madang just didn't

make sense. At least the ADF needle indication was still pointing

ahead and we still had the Huon Gulf coastline on our right.

I revised my guesstimated ETA to Phil: "Zero eight".

But had we

passed Lae without seeing it? Were we now heading for the 9000

feet mountain range? Through the deluge I tried to pick up the

first indication of a change in direction of the coastline towards

the south. I would know then that Lae was behind us. But then...

Jack saw it

first. He looked towards me and pointed ahead. I leaned across

to see better through the starboard window and there it was: the

Bureau of Meteorology's cloud searchlight. And - runway lights!

Unbelievable!

And the time? 1810!!

Because night

flying was not permitted in PNG and because Adastra aircraft generally

only flew in excellent weather and always landed several hours

before last light, I didn't consider the possibility that Lae

was equipped with runway lighting. It seems ridiculous that I

had operated from Lae for about six months without being aware

of this installation.

What an unexpected

bonus! We were almost over the runway at a height of 50 feet

or less when it was first visible. Jack and I exchanged a glance

of relieved understanding and he then returned to the cabin to

strap himself in. Thanks, Jack. A big sigh. Perhaps we'll live

to fly another day!

At about this

time, there was a change in my feeling of detached calm. It was

still there to the time we landed; but there was a gradual change

- difficult to explain - a change back to my normal perception

though my "back to the wall" mental concentration remained

throughout.

We crossed

the runway at right angles close to the 32 landing threshold.

I immediately reduced power and commenced to turn left. Phil

was right. Poor weather was an understatement. It was way below

the circuit minimum required for VFR aircraft - 1500 feet cloud

base and visibility 3 nautical miles. No good for IFR either.

There was no

way I was going to lose those runway lights. This would be very

much a modified circuit pattern. I reduced speed for initial

flap extension, 107 knots, and selected flaps down. They began

to extend and then stopped at only 5 percent! Oh shit. A hydraulic

failure. I could do without this.

It meant virtually

a flapless landing on a runway with minimum length for the Hudson

for a normal flapped landing. No time or inclination to try to

sort this one out in flight under the conditions of lousy weather

and approaching darkness. It probably couldn't be sorted out

in flight anyway and I needed to concentrate totally on staying

out of the water and not losing sight of the runway. It was a

relief that I had selected the landing gear down much earlier

and there was a safe (green) gear indication. The landing gear

was operated by the same hydraulic system.

Propeller pitch

full fine - a normal pre-landing procedure for a possible go-around.

There’d be no go-around but, without flap, I would need whatever

drag I could get to stop in the available runway length and fine

pitch would help. Selected early it would reduce actions necessary

on final approach.

The port wingtip

seemed almost to skim the water as I continued the left turn,

looking back over my left shoulder through the open side window

to keep the runway lights in sight. It was a continuous turn

through 270 degrees and I was then aligned with the 32 runway,

with the Tenyo Maru ahead to our left.

At some stage

Phil cleared us to land. An academic instruction at this stage

- we would be landing ready or not! To land, I needed to look

ahead through the rain splattered windscreen. It was like looking

through frosted glass. The misshapen appearance of the runway

lights through the heavy rain on the windscreen was far from their

normal crispness; the lights at the far end of the runway were

barely visible. Oh for some windscreen wipers right now! But

at least the runway lighting array was in reasonable perspective

for landing.

I kept the

indicated airspeed at 105 knots. Anything less without flap,

and with anything other than gentle control movements, could result

in a stall. The approach of necessity was very shallow but we

were stabilised in the slot for landing with engine power a little

above idle and we would be on the ground in about 8 seconds.

And then -

Holy bloody catfish!! The runway lights disappeared and I was

looking up at the dark shape of the Tenyo Maru beside us! It

felt as if a sudden downwash of wind off the end of the runway

was forcing us down and we were below the level of the runway!

My right hand

was on both throttles and I slammed them forward. Fortunately

both engines responded; an engine failure now would be disastrous.

It was a "go around" situation for a second approach

but this was out of the question. I knew there were cloud covered

hills to the west which were obscured by heavy rain. Going around

just wasn't on. The burst of power was for only 3 or 4 seconds,

enough to lift the aircraft above the level of the embankment

at the approach end of the runway.

I closed both

throttles almost immediately because of the need for a low approach

over the runway threshold without flaps. We cleared the embankment

at little more than flare height; we were perhaps 5 feet above

the runway threshold. With throttles closed, I eased the control

wheel back slightly to flare the aircraft and we were on.

Surprisingly

it was a smooth touchdown. We ran through to the far end of the

runway, quite easily done without flaps! But at least we stopped

in the available length. The wind, which almost had us in the

water from the eddy spilling over the end of the runway, was a

bonus during the landing run and allowed us to slow from the higher

landing speed necessary for a flapless approach. We landed about

25 minutes before the end of official daylight but, by the end

of the landing run, it was too dark to read the instruments. I

taxied the aircraft along the taxiway through the downpour in

the semi darkness to our usual parking position and shut down

the engines.

SOME INTERESTING

ASPECTS

By this time

the feeling of total calm had left me. I was having a controlled

attack of the heebie-jeebies.

I went to the

control tower to thank Phil for his help, in particular for the

runway lighting, without which we would not have seen Lae. I was

surprised to see Jack Tierney there. He shook my now trembling

hand and said: "Am I glad to see you! We thought you were

gone. When you climbed up out of the water you disappeared into

cloud."

Interestingly,

Lae Tower was the only "tower" I have seen which was

at ground level. It was situated to the north of the runway,

about midway along. From memory it was built on housebuilding

piers; the floor may have been 3 feet above the ground.

Even though

it appeared to Jack Tierney that the aircraft entered cloud, it

didn't, but his comment gives an indication of the local weather

conditions. A flapless landing requires a higher than normal

approach speed and the aircraft needs to be lower over the threshold

than normal even when landing on a runway of adequate length.

And when the runway is around the minimum length needed for a

normal flapped landing, there is little margin for error when

landing without flaps. That is, the least height over the threshold

with safety is making the most of the available landing length.

I lifted the

aircraft just enough to clear the embankment. I believe we cleared

it by about five feet. Jack McDonald said later: "I thought

we went through it!" (It's the only time I have ever needed

to climb an aircraft on a landing approach to flare height!).

Jack Tierney's comment "you disappeared into cloud', was

somewhat remarkable, especially when his viewpoint was near ground

level and only about 2,000 feet horizontally from us. His view

was probably obstructed by some intervening low scud.

After Jack's

generous greeting, Phil, who was then off duty and about to leave

the tower, was not so affable. He said: “I suppose you think

you are a bloody hero." His comment was like a body blow.

I said: "Phil,

the forecast looked good and so was the actual weather at Lae

when I filed my plan at Madang. There's no way I would have come

to Lae had I known what the weather's like."

Phil seemed

a little unsettled from his usual aloof self. I think he was

unwinding after preparing for a possible prang on or close to

the aerodrome. It was unusual that he had asked Jack Tierney

to come to the tower. He probably had in mind Jack's usefulness

in the event of an accident - knowledge of crew etc.

Phil softened,

and when we discussed the situation a little more, he indicated

that he had been calling us on HF from the time we reported at

the half-way position, telling us to go back to Madang - that

Lae was closed because of adverse weather. He was receiving our

HF transmissions and he was unaware that our HF receiver was faulty.

Even though I had transmitted on several occasions that we were

not receiving on HF, he somehow had the idea that we were.

Phil also mentioned

that the Mandated DC3 aircraft which had left Lae for Madang early

in the day was the only aircraft to depart from Lae all day.

The low cloud and heavy rain had moved in soon after its departure

and there had been no significant improvement.

When I'd spoken

to the Lae forecaster and obtained the actual weather conditions

at Lae before taking off from Madang, it was during the only 15

minute break in the weather all day. The weather closed in again

soon afterwards with persistent torrential rain.

There is often

a reluctance on the part of weather forecasters to change their

original forecast and there was no mention of anything other than

suitable conditions when I spoke to him. He probably believed

the break in the weather was consistent with his original forecast

and that the improvement would continue.

We must have

been very close to the sea surface when we encountered the downwash

on final approach. Had the flight terminated in the sea near

the Tenyo Maru we would have joined the earlier Hudson when it

had rolled over and crashed in almost precisely the same position

some years before.

The height

of the Hudson is 11 feet 10˝ inches from the ground to the top

of the pilot's compartment. The pilot's head would be about 18

inches below the highest point of the compartment. That is, sitting

in the control seat with the aircraft on the ground my eye height

would be about ten feet above the ground.

On final approach

when my eye level was below the level of the runway lights, the

wheels would have been ten feet or more below the level of the

runway. When the runway reference point was eleven feet above

mean sea level it didn't leave much margin. Tidal movement at

Lae is only a few feet, but perhaps it was low tide, or perhaps

the end of the runway was slightly higher than the runway reference

point. In any event we were bloody close!

Jack Tierney

drove us to the DCA mess in the Adastra Jeep. We were the last

to arrive for the evening meal and, still unwinding from the recent

events, my appetite was somewhat subdued. I mention the evening

meal only because of something Brian Smith did which was unusual.

We had eaten

our main course and dessert was being served. Brian was sitting

next to me and he received his plate of dessert first. He passed

it to me - as if to say: "Thank you." Totally unnecessary,

my sense of self-preservation had been working overtime. It was

a simple, unexpected, gesture. I didn't feel like eating dessert

(unusual for me!) but I did anyway.

Also during

the meal, Brian, having done some Private Pilot training, said

he thought we were in quite a difficult situation. In the cabin

he had been listening to the radio transmissions with headphones.

He said he was surprised at how calm my voice sounded and, because

of this, he thought perhaps it wasn't as bad as it looked. His

comment about the calmness of my transmissions was confirmation

to me of the strength of this strange tranquillity I had experienced.

I didn't have the heart to tell him that at that stage I had written

us all off. I made some inane response that I wouldn't want to

repeat the performance before breakfast every morning and left

it at that.

But this unusual

calm feeling, change of perception, change of consciousness, serene

peacefulness, call it what you will, needs to be experienced to

be believed. It was about six months before I felt comfortable

about mentioning it to anyone, even though the experience was

rarely far from my thoughts. It was so unexpected, so inconsistent

with the need for intense concentration and rapid, positive responses,

and it was just suddenly there. Where did it come from? Outside,

inside? It was certainly an internal experience which I found

to be a distinct advantage in the circumstances.

I have since

heard of other people experiencing something similar in life threatening

circumstances when death seems imminent and inescapable.

I wonder whether

it's a kind of internal reaction, common to all life forms in

near-death circumstances. For example when a mouse "freezes"

before being swallowed by a snake, is it suffering from shock,

has it given up on its future existence, or is its state of immobility

an indication of some internally produced anaesthesia?

My experience

seemed to be beyond panic and, apart from the acceptance of a

remote possibility of survival, I had virtually given up on our

future existence. However the feeling was by no means immobilising.

As well as being grateful that we survived, I am grateful to have

had the experience.

Many changes

have taken place in Papua New Guinea since 1962. In recent years

the Tenyo Maru slid into deep water and pilots were deprived of

a valuable approach aid. But Lae no longer exists as an aerodrome

either. It was disbanded in favour of Nadzab some years ago,

Nadzab being about 20 miles inland, in the Markham Valley. On

recent maps Cape Cretin, near Finschhafen, has been renamed "Schollenbruch

Point."

Jack McDonald’s

"fright" in VH-AGX was not the reason he didn’t fly

in Lockheed Hudson aircraft again. The company insured aircrews

against the possibility of accident but they did not insure Jack.

Had he been involved in an aircraft accident there would have

been only workers, compensation. So Jack's decision not to fly

applied to all Adastra aircraft. Jack flew often in airline aircraft

and, being Jack, he did in fact fly, uninsured, in the company's

DC3 when he was called upon for other technical problems in the

field.

And now that

there is only an occasional Lockheed Hudson flight anywhere in

the world by carefully qualified enthusiasts who have temporarily

brushed the museum dust off its wings, I believe I am safe in

claiming, with doubtful honour, that Jack's final Hudson flight

was with me.

Sincere thanks

to Jack McDonald and Brian Smith, who calmly and helpfully shared

the experience with me.

Sincere thanks

also to my sister Laurel Dumbrell, to Mike Wood, to Jack McDonald

and to Margaret for proof reading several drafts, to Dean Darcey

and Gordon Phipps for clarifying the accuracy of Papua New Guinea

aeronautical information, to the unknown Madang photographer, to

Phil Graham whose illuminating actions saved the day, to fellow

members of the "RA Club" for their encouragement, and

to Margaret for her helpful comments and for cheerfully accommodating

disturbed nights while I wrote and re-lived this episode from many

years past.

And thank you

Jack for getting our saturated engine started. Had it taken you

20 minutes longer there would have been no story to tell because

we wouldn't have flown that day. But please don't be so darned

efficient next time!END This manuscript can be read in different ways.

Acknowledgements: lst Australian rights only. (c) Copyright W.H. Bowles June 1995 |