|

The APR installation was fitted to

Hudsons VH-AGX, VH-AGS and VH-AGJ at various

times. The equipment consisted of a dish inside the bomb bay directed vertically

downwards through a circular cut-out in the bomb doors. This aperture was covered

externally by a removable fibreglass panel.

To calibrate the equipment on the ground, the bomb bay doors were opened and a

reflector at 45 degrees was placed underneath along the fore/aft axis of the fuselage.

A target was placed at a known distance and the calibration made. In the interests

of sperm count it was advisable not to pass in front of the gear when it was operating!

The technician's equipment in the aircraft was set up on the port side of the

main cabin, immediately behind the forward bulkhead. All the electronic gear (valves

in those days), with an oscilloscope was set up on Dexion shelving, and was about

five foot high by four wide. In the center, facing the technician was a continuous

rolling chart on which a pen marked a line showing the profile of the ground directly

underneath the aircraft. The center-line of the chart represented the datum height.

A Vinten 35mm film camera pointed down through the floor on the starboard side

of the bomb bay, next to the dish and had its own access panel for changing film

etc in flight.

The purpose of the APR was to confirm the terrain profiles that had been determined

from previous photographic survey and were usually carried out over the more remote

areas where land survey was impractical. The flight lines were usually drawn on

a series of these photographs that had been taped together to form a long roll.

Navigation was carried out using a standard drift sight that protruded through

the floor just aft of the nose perspex. This had a graticule along the fore/aft

axis and a prism under the instrument that could be tilted to give a view anywhere

from the forward horizon to just forward of the aircraft's position. With the

prism turned fully back, one had a vertical view of the ground beneath and it

was in this position that the drift was ascertained. APR work was carried out

at 10,000ft and once at operating height I would take a drift reading on a heading

appropriate to the datum airstrip. The aircraft had to be flown, as accurately

as possible, down the center line of the airstrip for a datum check to be made.

This could be the base strip or another in the area, the profile of which was

known from ground survey. The equipment would be running on the lead up to the

runway and I would note the heading from the gyro compass repeater in front of

my position in the nose. I would warn the technician of the approach of the threshold

("start datum coming, coming, datum….. NOW") whereupon the tech would mark the

chart accordingly. At the end of the runway I would then call "end datum….NOW"

and the chart would be marked again. From the time that the initial datum run

was started, until such time that a similar procedure was carried out at the end

of the sortie, I had to note the time and new bearing of every change in heading.

If the first datum run was not deemed accurate, the pilot executed a procedure

turn and a reciprocal run was made. This was repeated, hopefully not often, if

this was also unacceptable.

If all was well, and a recognizable profile of the strip had been recorded, I

then gave headings to take us to the start of the first survey run. Another drift

check was made before the start of the run and the aircraft was lined up on the

calculated heading near the start point. The technician would be aware that the

start was close and would have the equipment running with the run details marked

on the chart. A view ahead through the drift sight prism would show whether the

aircraft was lined up to pass over the start point and also any feature along

the intended track. If not, I would call heading corrections. All things being

equal, I would then call "start point coming, coming, start point….. NOW" and

the technician would mark the chart accordingly. The end of the run was treated

the same way. From then on it was a case of navigating the aircraft as close as

possible to the flight lines drawn on the photos or map. I would check the drift

from time to time and ask for heading corrections if needed and also call out

any features on the ground that I thought would make a prominent deflection on

the chart, say an escarpment or creek. The autopilot* on the Hudson was very stable

and, if the conditions were right, long distances could be covered without any

corrections being made. Heading corrections were kept as small as possible and

were usually of one or two degrees, which just needed a touch of the autopilot

knob. The main problem with APR work was turbulence, which could build up very

quickly in the remote areas and many flights were cut short because of it, as

a change in attitude would give false profile readings on the chart. The final

run over the datum airstrip at the end of the sortie had to be as accurate as

the first and in lumpy conditions it was sometimes quite tricky for everyone.

Without it, all would be wasted.

Survey flight times could be anything up to six hours on a good day but the norm

was usually about four. I have many flights of 1 to 2 hours that are listed as

"Attempt Survey" and these would most likely have been cut short because of the

conditions, the equipment usually being pretty reliable.

(* Rick Geary recalls that Hudson VH-AGJ was not fitted with an

autopilot and consequently APR surveys in this aircraft had to be hand-flown!)

| Hudson

VH-AGS in APR configuration with bomb bay doors

open. [Photo: Owen Smith] |

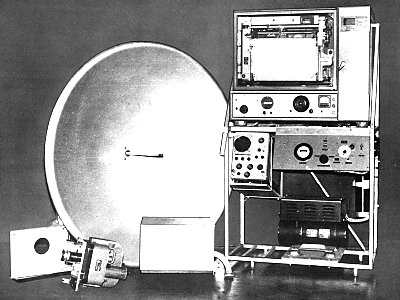

| The

APR installation in the bomb bay of Hudson VH-AGS.

Note the circular cut-out in bomb bay doors and the fibreglass

cover for the aperture. [Photo: Owen Smith] |

| The cabin

of Hudson VH-AGS showing the APR operator's position

to port. [Photo: Owen Smith] |

For a

further description of APR, please refer to:

Australian Aerial Survey Review

|

![]()